Revive

Revive

Lacemaking was well established in Salisbury by the 1600s and was later centred around the village of Downton.

The industrial revolution caused many of these specialised local industries to die out. Yet the tradition of making Downton lace was revived at the beginning of the 20th century by two local women, Mrs Robinson and Mrs Plumptre.

Object in focus: Downton lacemaker’s doll

‘A Downton lace doll tells her story’ By Pompi Parry, Look Again project volunteer.

“Hello, I am a small Downton Lacemaker doll, I’m made from pipe cleaners so I can sit down on a seat in front of my lace pillow. I was made near Aylesbury in Buckinghamshire, another Lacemaking area, by a student of a well-known lace teacher in that area, Miss Dawson, as a gift to Miss Edith Glyn of Salisbury.”

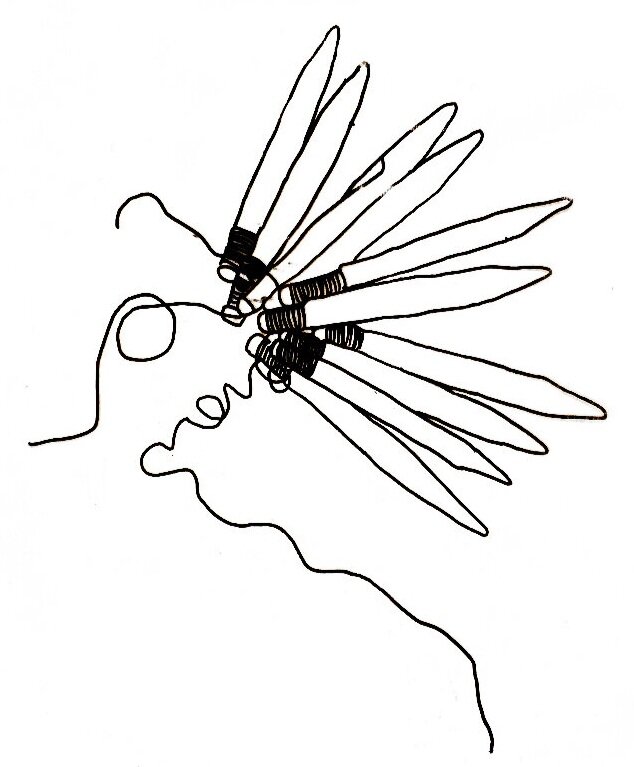

Young person’s drawing, bobbins, ©The Salisbury Museum collection

Miss Glyn had been involved with the Downton Lace Industry since 1921 and its secretary from 1935 until its closure in 1966 just a year after I arrived in Salisbury.

When the Industry closed, Miss Glyn kindly found me and a wealth of documentation about the Downton Lace Industry, a new home at the Salisbury Museum.

I show, albeit in miniature, what a Downton Lacemaker would have looked like working at her lace.

The large blue sausage-shaped object in front of me is my Lace pillow which is very firm and stuffed with Barley straw. The pattern, called a Pricking, is pinned firmly on to this pillow.

It is called a pricking because before I can start to make the lace pinholes have to be pre-made depicting the design.

These prickings used to be made from parchment, but now a firm card is used. The best lace is made using Linen thread, though nowadays cotton is often used instead. The fineness of the lace dictates the thickness of the thread used. Each thread is wound onto a Bobbin – you can see these hanging over the back of my pillow.

When I am making lace, the bobbins would be in front of me so I can work them with my hands. I twist or cross the threads in a weaving process, placing one pin at a time into the premade holes so supporting the threads and create the pattern. Our bobbins are a shape which is unique to this area.

Lace Maker doll, ©The Salisbury Museum collection

The bobbins were all made by hand, using local hedgerow woods, some whittled others turned on a lathe. Many were left plain, but many others were decorated in various ways. Dates, initials, messages or small motifs of birds, plants, hearts, suns etc. were scratched or chipped into the bobbins, sometimes the scratchings were filled with coloured wax.

Nitric Acid, commonly known as Aqua Fortis was also used to create decorative patterns - we nicknamed these bobbins Agnes Forte bobbins.

The decoration on the bobbins doesn’t have any relevance to the making of the lace it just makes the tools of our trade more fun to work with or so we can identify our bobbins. They could have been a special gift from a loved one.

I said earlier that the Downton Lace industry closed in 1966, this was really for two reasons, lace was not being used in the fashions of the mid 20th Century, and the ladies who had been making the lace that the Industry sold were all now elderly, and there was little reason for the younger generation to learn the skill.

At the end of the 19th Century, the story had been much the same, though it had been the competition of cheaper machine laces which was the cause then.

A letter in the Salisbury Museum’s archive demonstrates this. Mrs A. G. Taunton, who was born in Downton in 1823, wrote to her granddaughter Olive Pye-Smith in 1891, saying “Dearest Olive, I am sending you a small piece of lace which Grace Cooper has made and which I want you to keep until you are as old as I am as by that time few of the younger folks will scarcely know what lace pillow and bobbins mean when you will be able to say you have seen the lacemaker at work.”

Luckily there were two other ladies, new to the area, who were equally worried and set about the task of saving this centuries-old local tradition from falling into obscurity. In 1898 Mrs Plumptre, wife of the new vicar moved into the vicarage and Mrs Octavius Robinson who had arrived a few years before to live at Redlynch House. They visited the, now very elderly, remaining lacemakers collecting samples of their work and learnt all they could from them. Mrs Robinson’s two daughters were taught by Mary Harrington and Anne Martin. Mrs Biddlecome was another of the old lacemakers, and her daughter did all the household chores so her mother could make the lace.

Mrs Plumtre started giving classes firstly under the County Council’s Night School regulations then when the scheme was discontinued, she continued privately at the vicarage and later also in Charlton.

Mrs Robinson also ran classes at Redlynch house.

In 1901 Lady Radnor founded the Downton Home Industries which provided equipment and sold the produce, of not only the Lacemakers, but also other local crafts such as spinners, weavers and glove knitters.

In 1909 she asked Mrs Robinson to take over the responsibility of the Lace industry and from then on, it became an independent enterprise.

Gradually over the next few years, classes were started in several other locations including Bramshaw, Minstead, Calmore, Lyndhurst, Downton and Landford.

Many of the children who were taught in these classes went on to become the main workers, several continuing to make lace long after the closure of the Industry in 1966.

Lace Maker doll, ©The Salisbury Museum collection

Perhaps another time I can tell you their stories and those of the many other ladies, teachers, lacemakers, administrators and patrons who were involved in the success of this Industry.

By Pompi Parry, Look Again Project Volunteer.